*This article was originally written and published on Medium: Article Link

Imagine rowing by yourself in the middle of a river before the sun comes up. There are other boats from your team with you but it’s so dark that you can barely see them, even though they are just twenty meters away. The only light source comes from the car lights of the early commuters on the road beside the river and the faint glow of the waterside buildings that keep their lights on. A coach is following your team from a motorboat shouting commands to help improve your technique and speed. You can only make out the silhouette of your coach but hearing the commands allows you to keep focus and improve as an athlete.

The above situation may be a very ineffective way to train a group of athletes, but due to a number of reasons, this is what morning training sessions are like at the club where I coach. Training with low visibility is hard enough, but imagine if an athlete couldn’t hear their coach. This is the reality for one of my athletes who has a hearing impairment, who communicates primarily by reading lips. As rowing is a very technical sport, this makes it extremely difficult to provide the necessary coaching needed to improve.

Over the years of coaching this athlete, we have tried multiple solutions ranging from flashlight signals to texting commands, all with little success. The closest we got was by using a shared Google Drive document that automatically updated as I typed. An iPad was then mounted to the boat so the message would be easily visible. In theory, this solution worked great. I would simply write my coaching commands and they would appear on a screen for the athlete to read. However, after implementing and using this solution, it proved to have many flaws.

Due to the limited available spots to place the iPad in the boat, the athlete had to be looking down to read the screen. This caused a problem as rowers should be looking straight in front of them, not down at their feet. It became a bit of a conundrum. The athlete would either look down too much and begin row poorly or not look down enough and miss the commands needed to help improve technique.

As a coach, this solution was also not ideal. Being in the coach boat alone, I had to juggle timing with a stopwatch, shouting commands through the megaphone, and writing messages on my phone, all while driving the boat and observing the athletes. I simply didn’t have enough hands to manage everything. I tried voice to text for messaging the athlete, but like many sports, rowing is filled with its own unique terminology which my phone couldn’t understand. On a side note, this did lead to some very amusing messages with a meme being sent at one point.

What we had was a solution that worked but was not practical enough because of user experience issues. This is where the designer and developer sides of me came in. Why not just build an app that has the same core functionality but fixes the usability problems we experienced? That’s exactly what I did.

I call the app Vahi (Visual Aid for the Hearing Impaired) due to lack of creativity, but it is essentially a one-way messaging app that allows me to send messages from my phone to the athlete’s iPad in the boat. However, unlike using a Google Document, this app was designed to be used for coach to athlete communication.

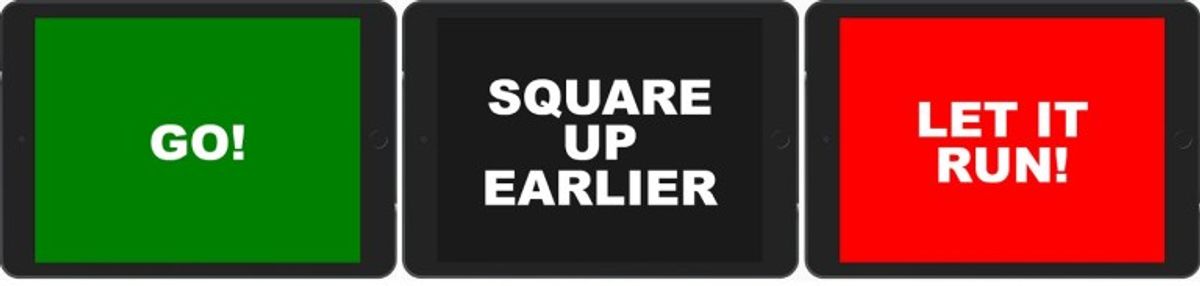

The athlete’s side of the app is very simple in design, large white text that is centered on a dark background. What makes it different is that upon receiving a new message the screen will flash brightly to catch the athlete’s attention. Instead of always having to keep an eye on the screen, the athlete now only needs to look at the screen when it flashes. I also incorporated the use of colour for the basic start and stop commands. A green background will appear when the word “Go!” is sent and a red background will appear when the words “Let It Run!” are sent. “Let It Run!” is a rowing term for “Stop”. This way the athlete doesn’t even have to read the messaging to know what it says.

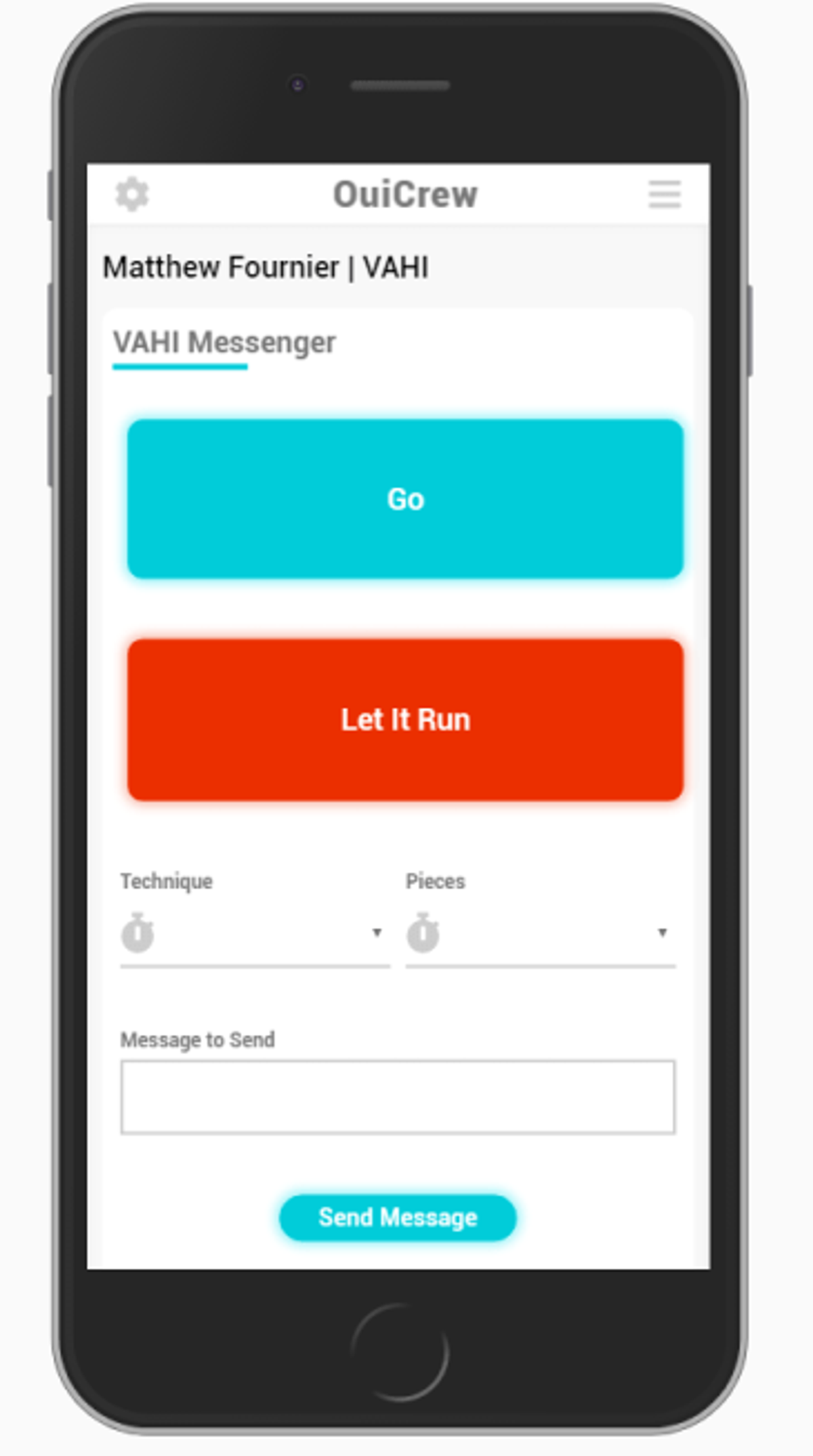

As mentioned previously, the biggest problem on the coaching side was trying to send messages while juggling other coaching tasks. To solve this I designed the messaging component around the need to send messages quickly and efficiently. To achieve this I decided that there would be three levels of messages that can be sent, each having its own attributes. Urgent, Quick, and Custom.

Urgent messages are… well, urgent. This is used if the athlete needs to be signaled to start a training piece, or more importantly, stop if they are about to collide with something. These messages need to be sent as quickly as possible. To allow for this, there are two big buttons that when pressed will instantly send the athlete a message. The buttons are big, to be easily found and pressed. They are also colour coordinated to match their messages. This design makes signaling to the athlete as quick as pressing a button.

Quick messages are used for the bulk of coaching the athlete. A lot of coaching is saying the same thing over and over until the athlete makes it a habit. As such, I made a collection of common coaching commands, categorized them, and put them into dropdown lists. To send a quick command I simply scroll through my list and select one.

There are times when I need to send a message that isn’t on my pre-compiled list. For this, there are Custom messages. These are not usually time-sensitive so the implementation is just a standard text input box with a send button.

The app I built is not a perfect solution but it does fix many of the main usability issues that were encountered in previous alternatives. More importantly, it allows me to communicate with the athlete, and in turn, helps the athlete improve.

If you have had similar issues when coaching hearing-impaired athletes, I would love to discuss how you solved them. Also, don’t hesitate to reach out if you think this app would be beneficial to one of your athletes.

Thanks for reading ✌️